Allison's Gambit: Interview with Author Dr. Chris Price

We recently had the opportunity to speak with family physician and author Dr. Chris Price about his new book, Allison's Gambit. Dr. Price talks about the influence Alzheimer's disease had on his writing and outlook as a doctor.

Connection to Alzheimer's

Obviously, you have been touched by Alzheimer's disease. Can you tell us more about your experience with the condition? What made you decide to write a book about this experience?

I had an experience with Alzheimer's at a very young age. It was my first year in college, and I took a job as a respite caregiver. Her husband couldn't be left alone. It was eye-opening. My shift was 4 hours per week, and she took the other 164 hours.

It's only in retrospect do I realize how disparate this really was. Once she trusted me, she was gone almost the minute I arrived. Two things I remember clearly about this experience:

- The daily walk. He could only walk for about 20 minutes, which meant you had to turn around after about 10. He could get quite defiant, but in time, I became better at distracting him.

- Our game of chess. Most days I did a variety of things, such as playing music and reading to him. I recall he really enjoyed flipping the pages of magazines. He didn't really speak, and so it caught me totally off guard one day when I moved a chess piece. He immediately played the opposite color. And he moved correctly. We must have done 10 or 15 moves and then...he stopped. It's like the light that came on suddenly went out. He never played chess with me again.

A startling philosophy

You provided this quote: "I recently buried my mother, who I took care of for 6 years with Alzheimer's dementia. I never want to live like that. I never want to ask someone to care for me like that. So I'm going to smoke so I die of something else... Before I lose my mind."

Tell us more about the person who inspired your main character.

One thing that's great about family practice is on any given day a patient will surprise you. Typically, it is regarding a diagnosis. In this case, it was a philosophy.

My patient wanted to die young. As you can imagine, from the moment you start medical school, you learn countless reasons patients should stop smoking. Different techniques are instilled to help the provider encourage a patient to quit. What was different about LT, the patient who inspired the main character in Allison's Gambit, is that she was so adamant. In her case, it was the fear of Alzheimer's disease and the dependency that was greater than death itself.

What she showed me was the raw emotion that she had from taking care of her mother. And she made it very clear: She didn't want to put anyone else through a similar experience caring for her. Finally, she said that she "just knows" that she will develop Alzheimer's if she lives long enough. So, smoking seemed like the best solution.

As the weeks passed after this conversation, I started to empathize with LT. I began to explore the concept of her philosophy. A goal to die young to not only prevent being a burden but to prevent losing the capacity to experience and love.

What if we had a choice?

As a doctor, you have a very unique perspective. End-of-life care is difficult for most people to wrap their heads around – it is grim, sad, and typically avoided entirely – until a crisis hits. What kind of role do you play or try to play when you encounter people who are touched by Alzheimer's, whether as a patient of Alzheimer's themselves or as a caregiver?

Soon after this visit, I began to write. I began with what I started to recognize as a truth that is completely ignored: We are all going to die.

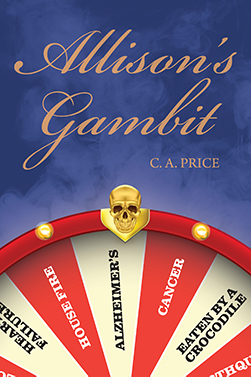

Frankly, most manners of death are unpleasant. If one could choose, are there some we would prefer not to take? I must thank my publisher Vinnie Kinsella for the cover. With just this visual, a wheel of fortune where the only choices are different ways of dying, it captures this concept perfectly. From this I began to realize, LT's philosophy actually makes a great deal of sense.

What distinguishes dementia is the "What is the point of it all?" question. When a person doesn't seem to recognize their surroundings or participate in life as they had before. It is this aspect that brought such incredible fear to my patient, LT.

Diving deeper into the caregiver experience

How has the experience of writing Allison's Gambit changed your perspective? Did you learn anything along the way? If so, what?

After beginning the writing process, I started to recognize the caregiving aspect. I hadn't really noticed how often a patient struggled with taking care of their parent. Or dealing with a spouse who was taking care of their parent. What I realized is that people didn't come to the doctor to share their caregiving issues. Instead, it would be a comment that would be dropped when asked, "Why didn't you get your labs before today's appointment?"

Once I was looking for it, I began to hear it everywhere. Instead of just pressing forward and asking them to get their labs sometime in the next few weeks, I began to explore how they were struggling. It became eye-opening. Further, you can't help but realize there aren't any easy solutions.

Often a long journey

One thing I bring is perspective. The initial concerns of poor memory later turn into a confirmatory diagnosis, then medicines, caregiving, and eventually death. Two patients, I recall clearly. Not only because of how they presented, but also helping them and their families through the process of what was to come.

A relatively young high school principal

He was starting to forget things. It seemed that he might be overreacting, as he was still functioning in a high-stress, very complicated job. Soon after he left, my assistant informed me that he had left his phone in the room. Of course, we couldn't call him, so we had to wait until he figured out where he had left it. It took longer than one would have expected.

A woman like Bea Arthur, one of the Golden Girls

She felt she was having an issue with her mind because she could no longer do Wednesday's New York Times crossword. I thought, "I can hardly do Wednesday's crossword," so it didn't seem notable. Until she then informed me that she used to be able to do Saturday's crossword. Well, anyone who knows the NYT crossword puzzle knows Saturday's puzzle is fiendishly difficult.

This truly was a concerning change. Yet one that wouldn't show on a classic test. Her other issue was that she could no longer sight-read piano music like before. She progressed rapidly. Within months, she donated her grand piano to the local university and gave me a bunch of her piano music.

A changing landscape

Recently, about 5 years ago, Medicare has requested that we do a mental status evaluation on every patient over 65, every single year. As a result, I have done a lot of these tests. I write about this very clearly in the book because it can be so difficult to watch. In my experience, it is much harder to endure when you are a family member.

When I was in medical school, I would learn of a disease, and you would hear something like, "Average life expectancy, 57 years." And I would wonder why? The causes just aren't all that obvious.

After being a physician now for roughly 25 years, I have come to understand the end of life much better. Something as simple as pneumonia that would have been an annoying 2-week illness to a healthy person could lead to hospitalization in someone with an underlying disease.

I feel the role I play is to help patients and families recognize there are different paths that are all caregiving. Providing antibiotics, oxygen, chemotherapy, music therapy, cardiac defibrillators, compassionate morphine... All of this is caregiving. What is clearly difficult for those to see is when the more aggressive treatments aren't yielding positive results.

In fact, it becomes burdensome and painful. I feel it is my role to help a patient and family realize when doing less becomes a more positive experience.

Feelings are okay!

The larger social battle with Alzheimer's is the stigma and isolation that can occur, especially as the disease progresses. Your new book speaks to that perfectly with the main character who is essentially setting out to self-destruct. Alzheimer's is so devastating, and caregivers really get a front-row seat, watching someone they love transform from one person to someone entirely different. What advice would you give to a new caregiver or someone newly diagnosed with Alzheimer's?

This is the crux of the novel. Negative feelings are okay! Anger is okay! Because in reality, these are all feelings that come every day with life.

What is not okay is to presume these feelings need to be borne alone. What is not okay is that we aren't spending more time trying to find ways to make the life of those with dementia significantly better. What is NOT okay is that we are turning to expensive, lonely nursing home care early without finding better ways to keep patients in their community.

I think we need to similarly try and put together resources for those with dementia. Adult daycare centers should be everywhere. Much clearer training to doctors on how to manage the early stages. More emphasis is placed upon comfort rather than complicated medical regimens. Greater discussions on how to manage sundowning and aggression. And finally, better use of hospice and comfort care.

I believe it is through talking about these shared, albeit difficult, experiences that we will provide better care in the future. That was the primary goal in writing this book.

Join the conversation