What's the Story with Napping and Alzheimer's?

You hear one day that daytime naps are good for your health. Then, the next day, you hear that daytime naps are problematic.

Discussions about nighttime sleeping and daytime napping frequent the spaces on the internet. Let’s unpack the relationship between sleep and wakefulness as it relates to Alzheimer's disease (AD) through the lens of daytime napping.

Sleep and Alzheimer's

Sleep health continues to be an area of focus for AD research. What’s known:

- Specific kinds of neurotransmitters regulate our sleep-wake cycle

- People with AD develop clusters of toxic proteins (amyloids) which can disrupt that cycle1

Let’s face it, anyone who loses sleep, regardless of neurological health, will be sleepy the next day. That’s because our sleep-wake cycles are informed not only by circadian rhythms but by something known as sleep drive or sleep pressure.

As with hunger, sex, or thirst, the sleep drive builds upon the body’s most recent opportunity for sleep. When sleep is inadequate, the body will build up a drive to sleep during the day to correct that imbalance.

When AD strikes, however, sleeping habits can shift for biological reasons. Some people will:

- Oversleep, day and night

- Undersleep

- Sleep at night, but only in fits and starts

- Awaken repeatedly and behave oddly (wandering, shouting)

Wakefulness and Alzheimer's

We can’t really talk about sleep problems, however, without also talking about wakefulness problems.

The sleep medicine community recognizes that one of the telltale signs of hidden or undetected health problems is the presence of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS).

People with AD are likely to need more sleep during the day because of the aforementioned impairments in the sleep-wake cycle related to sleep loss.

But the disease course of AD itself is also to blame for the sudden need to nap. Early-onset of AD is linked to a buildup of toxins (“tau tangles”) which disrupt the functions of neurons charged with promoting daytime wakefulness.2 For some with AD, up to 75 percent of their wake-promoting neurons were shown to be lost, in one recent study.3

In a sense, people with AD suffer losses from both sides of the sleep-wake process.

Being more mindful of increased napping

Worry may not be the right word. Perhaps we should be more mindful of increased napping, especially in our later years.

Napping, in and of itself, is known for its benefits, especially for cardiovascular health though even these rely on conditional factors like frequency.4

Also, the human body can experience multiple medical conditions, especially later in life. EDS is also linked to depression, a hidden sleep disorder, or any number of autoimmune diseases, for instance.

Possible connection between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's

Other prevailing problems for people later in life are glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, which can lead to type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Recent research shows trajectories for developing both AD and T2D to be stunningly parallel.5

Less sleep at night for any reason shortchanges us critical stages of sleep (REM sleep and slow-wave sleep, both assisting the brain in crucial ways).

For both T2D and AD, these losses create the conditions for glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. This spawns body-wide chronic inflammation, which, in turn, unleashes other unhealthy processes (such as increases in amyloid plaques and A1c levels). If ignored, these lead to full-fledged T2D and/or AD.

The vicious cycle continues in what’s termed a negative feedback loop, as both T2D and AD perpetuate ongoing sleep-wake problems.

Discuss any napping changes with your doctor

If you need regular naps during the day—and you believe you’re getting adequate nighttime sleep—talk to your doctor. You may need an overnight sleep study to rule out hidden (but treatable) sleep disorders such as sleep apnea. Fortunately, these can be treated, and treatment can greatly improve your daytime energy and nighttime sleep quality.

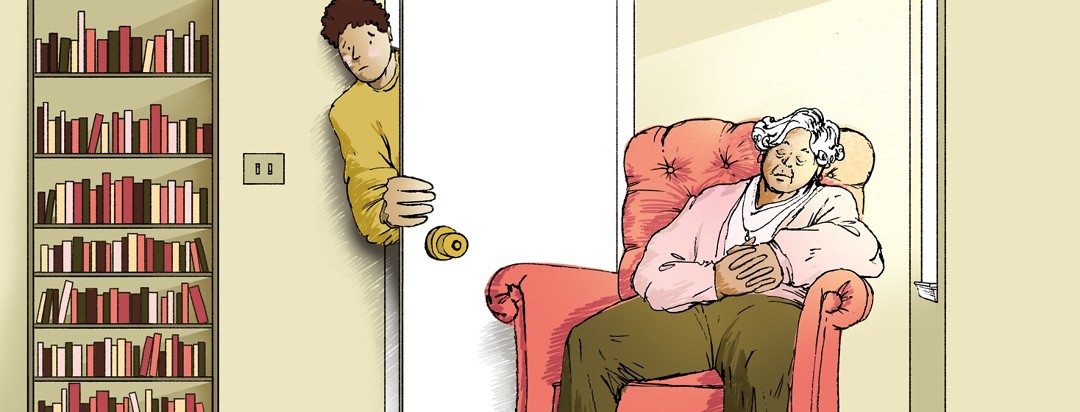

If you’re a caregiver of someone with AD (either diagnosed or suspected), and you notice they’re napping more frequently than before, encourage them to discuss these changes with their doctor. A good doctor will ask questions, run tests to identify potential root causes, and identify therapies or lifestyle changes to prevent EDS.

Meanwhile, consider following these napping safety tips from the National Institutes on Aging.6 For those who wander at night, prevent falls by:

- Keeping the home clutter free

- Installing supportive bars near the toilet

- Placing safety gates at stairways

- Having easy-access lighting (including non-LED nightlights)

- Lock up or refuse to stock over-the-counter sleep aids, which, when taken regularly, could worsen AD progression7

- Avoid smoking in bed

Join the conversation